the title probably says it all. when we covered media literacy for kids in a single slide out of about thirty slides, one point became the star of the show of edci336 on monday, october 30th. and that is the house hippo.

I was born in 1995 to a family that lived in front of the television, so the Concerned Children’s Advertisers was like a strange aunt or uncle who held sage wisdom but doled it out bizarrely and totally unprompted. It wasn’t just me – all of my friends loved to say, deadpan as if we were straight out of Britain, “my thing is bugs.” We could harmonize the chorus of “Don’t You Put It in Your Mouth.” No one wanted to talk about “Crack.”

I don’t think it’s a stretch to say the House Hippo is a favourite among Millennials – it’s probably the best remembered as it’s simultaneously the most palatable – offensive factor is at a firm zero. Yet I’d argue it’s totally unlike the other CCA commercials in that, out of more than two dozen educational and/or cautionary adverts, it uniquely did not communicate its point at all. The “Crack” commercial has a twist but takes no losses in its message. Meanwhile, we remember the House Hippo at best as reducing it to its (justifiably) cutesiness, or at worst so genuinely missing the point of the ad that it validates the concern. Case in point, the tangled knots of misinformation in media has escalated seriously as my generation has aged.

I have to start with making clear my admiration for the CCA – part nostalgia and part assessment, their demonstrated values were clear and they were often successful in using multimedia to communicate their messages to children nationwide. So how did the House Hippo fail? Some arguments in the comments of the original and a reboot of the advert (recognizing YouTube comments are not academic resources, but can represent general consensus pretty aptly) are clashing on whether the hyper-realistic portrayal of House Hippos were its demise, or if that too-good-to-be-true angle was necessary to show kids how essential it is to be critical of what we are consuming. A top comment points out that kids want to believe that it’s real, so they put doubts to the side. One comment describes, without detectable jest, finding a House Hippo nest in their college years – not sure what to make of that one.

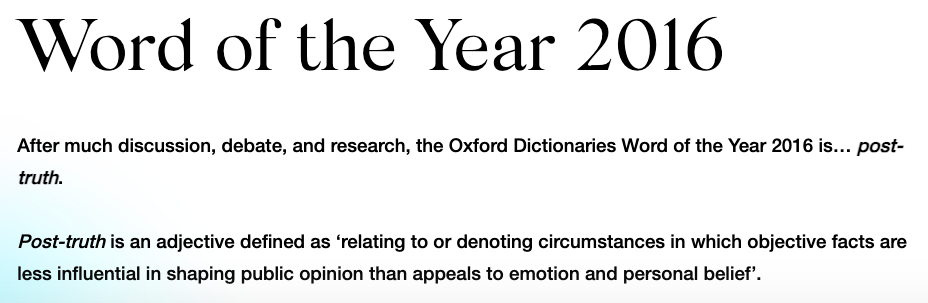

Some comments criticise the reboot for holding the narrative of what’s fake or not instead of giving kids the agency to decide for themselves. I feel two ways about this, especially approaching the topic as a future educator and eventual future parent. On one hand, neither the original or the reboot give any tangible instruction on what kids should do to be more critical thinkers or more media literate – it misses the weight of the well, what do you think??? as in the “Crack” commercial, for example – there’s no lesson in it. I think giving kids the open door of do you think this is real??? is ineffective because kids have – and are generally fostered to grow – wild, creative, committed imaginations. And then leaving truth in the eyes of the beholder has, in my view, been a massive player in our post-truth world.

At the same time, I understand a sense of hesitation when a company – backed by huge global conglomerates who, arguably, have business interests come first – states that they have kids’ best interest in mind and have the answers to make them the ideal citizen. Distrust for governing systems (overtly political or otherwise) feels rampant right now, especially with people around my age. Is this the critical thinking that the House Hippo offered?

All of that said – again, as an aspiring educator and parent – there is an inherent responsibility to pass on knowledge to generations beyond us. This is foundational in Indigenous knowledge systems as well, honouring that learning is embedded in memory, history, and story, and involves generational roles and responsibilities. Elders and knowledge keepers have taken up the sacred duty of working diligently to make sure children are brought up with aligned values of self, community, and land since time immemorial. Maybe the difference with the colonial west is that we have lost the consensus on values. That isn’t something that we can ask ourselves if we have been conditioned to hyper-individualism or material instant gratification. If we are concerned with how we are advertising to or advising our children, maybe we need to look beyond our purview and consult nations who have maintained values of cooperation and community longer than we can know.

Editor’s note: I sincerely apologize for the sheer degree of hyperlinks in this post. If you are at all interested in this topic after a first skim, I promise you they are worth the rabbit hole.